Slater-type orbital

Slater-type orbitals (STOs) are functions used as atomic orbitals in the linear combination of atomic orbitals molecular orbital method. They are named after the physicist John C. Slater, who introduced them in 1930.[1]

They possess exponential decay at long range and Kato's cusp condition at short range (when combined as Hydrogen-like functions i.e. the analytical solutions of the stationary Schrödinger for one electron atoms). Unlike the common hydrogen orbitals, STOs have no radial nodes (neither do gaussian-type orbitals).

Contents |

Definition

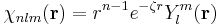

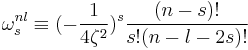

STOs have the following radial part:

where

- n is a natural number that plays the role of principal quantum number, n = 1,2,...,

- N is a normalizing constant,

- r is the distance of the electron from the atomic nucleus, and

is a constant related to the effective charge of the nucleus, the nuclear charge being partly shielded by electrons.

is a constant related to the effective charge of the nucleus, the nuclear charge being partly shielded by electrons.

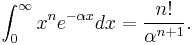

The normalization constant is computed from the integral

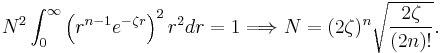

Hence

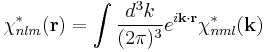

It is common to use the spherical harmonics  depending on the polar coordinates of the position vector

depending on the polar coordinates of the position vector  as the angular part of the Slater orbital.

as the angular part of the Slater orbital.

Differentials

The first radial derivative of the radial part of a Slater-type orbital is

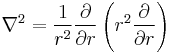

The radial Laplace operator is split in two differential operators

The first differential operator of the Laplace operator yields

The total Laplace operator yields after applying the second differential operator

the result

Angular dependent derivatives of the spherical harmonics don't depend on the radial function and have to be evaluated separately.

Integrals

The fundamental mathematical properties are those associated with the kinetic energy, nuclear attraction and Coulomb repulsion integrals for placement of the orbital at the center of a single nucleus. Dropping the normalization factor N, the representation of the orbitals below is

.

.

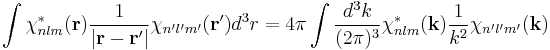

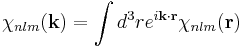

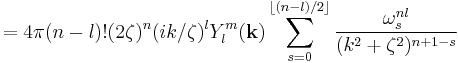

The Fourier transform is[2]

,

,

where the  are defined by

are defined by

.

.

The overlap integral is

of which the normalization integral is a special case. The starlet in the superscript denotes complex-conjugation.

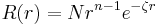

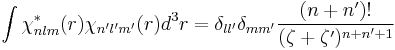

The kinetic energy integral is

a sum over three overlap integrals already computed above.

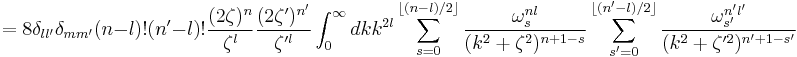

The Coulomb repulsion integral can be evaluated using the Fourier representation (see above)

which yields

These are either individually calculated with the law of residues or recursively as proposed by Cruz et al. (1978).[3]

STO Software

Slater type orbital (STO) basis functions are used in some quantum chemistry software. The fact that products of two STOs on distinct atoms are more difficult to express than those of Gaussian functions (which give a displaced Gaussian) has led many to expand them in terms of Gaussians.[4]

Analytical ab initio software for poly-atomic molecules has been developed e.g. STOP: a Slater Type Orbital Package in 1996.[5]

SMILES uses analytical expressions when available and Gaussian expansions otherwise. It was first released in 2000.

Various grid integration schemes have been developed, sometimes after analytical work for quadrature (Scrocco). Most famously in the ADF suite of DFT codes.

References

- ^ Slater, J.C. (1930). "Atomic Shielding Constants". Phys. Rev. 36: 57. Bibcode 1930PhRv...36...57S. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.36.57.

- ^ Belkic, Dzevad; Taylor, Howard S. (1989). "A unified formula for the Fourier transform of Slater-type orbitals". Physica scripta 39 (2): 226–229. Bibcode 1989PhyS...39..226B. doi:10.1088/0031-8949/39/2/004.

- ^ Cruz, S. A.; Cisneros, C.; Alvarez, I. (1978). "Individual orbit contribution to the electron stopping cross section in the low-velocity region". Physical Review A 17 (1): 132–140. Bibcode 1978PhRvA..17..132C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.17.132.

- ^ *Guseinov, I. I. (2002). "New complete orthonormal sets of exponential-type orbitals and their application to translation of Slater Orbitals". Int. J. Quant. Chem. 90 (1): 114–118. doi:10.1002/qua.927.

- ^ Bouferguene, A.; Fares, M.; Hoggan, P. E. (1996). "STOP: Slater Type Orbital Package for general molecular electronic structure calculations". Int. J. Quant. Chem. 57 (4): 801–810. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-461X(1996)57:4<801::AID-QUA27>3.0.CO;2-0.

- Harris, Frank E.; Michels, H. H. (1966). "Multicenter integrals in quantum mechanics. 2. Evaluation of electron-repulsion integrals for Slater-type orbitals". J. Chem. Phys. 45 (1): 116. Bibcode 1966JChPh..45..116H. doi:10.1063/1.1727293.

- Filter, Eckhard; Steinborn, E. Otto (1978). "Extremely compact formulas for molecular two-center and one-electron integrals and Coulomb integrals over Slater-type atomic orbitals". Phys. Rev. A 18 (1): 1–11. Bibcode 1978PhRvA..18....1F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.18.1.

- McLean, A. D.; McLean, R. S. (1981). "Roothaan-Hartree-Fock Atomic Wave Functions, Slater Basis-Set Expansions for Z = 55–92". Atom. Data Nucl. Data Tables 26 (3/4): 197–381. Bibcode 1981ADNDT..26..197M. doi:10.1016/0092-640X(81)90012-7.

- Datta, Shyamal (1985). "Evaluation of Coulomb integrals with hydrogenic and Slater-type orbitals". J. Phys. B 18 (5): 853–857. Bibcode 1985JPhB...18..853D. doi:10.1088/0022-3700/18/5/006.

- Grotendorst, Johannes; Steinborn, E. Otto (1985). "The fourier transform of a two-center product of exponential-type functions and its efficient evaluation". J. Comp. Phys. 61 (2): 195–217. Bibcode 1985JCoPh..61..195G. doi:10.1016/0021-9991(85)90082-8.

- Tai, H. (1986). "Analytic evaluation of two-center molecular integrals". Phys. Rev. A 33 (6): 3657–3666. Bibcode 1986PhRvA..33.3657T. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.33.3657. PMID 9897107.

- Grotendorst, Johannes; Weniger, E. Joachim; Steinborn, E. Otto (1986). "Efficient evaluation of infinite-series representations for overlap, two-center nuclear attraction, and Coulomb integrals using nonlinear convergence accelerators". Phys. Rev. A 33 (6): 3706–3726. Bibcode 1986PhRvA..33.3706G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.33.3706. PMID 9897112.

- Grotendorst, 1Johannes; Steinborn, E. Otto (1988). "Numerical evaluation of molecular one- and two-electron multicenter integrals with exponential-type orbitals via the Fourier-transform method". Phys. Rev. A 38 (8): 3857–3876. Bibcode 1988PhRvA..38.3857G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.38.3857. PMID 9900838.

- Bunge, Carlos F.; Barrientos, José A.; Bunge, Annik Vivier (1993). "Roothaan-Hartree-Fock Ground-State Atomic Wave Functions: Slater-Type Orbital Expansions and Expectation Values for Z=2–54". Atom. Data Nucl. Data Tab. 53 (1): 113–162. Bibcode 1993ADNDT..53..113B. doi:10.1006/adnd.1993.1003.

- Harris, Frank E. (1997). "Analytic evaluation of three-electron atomic integrals with Slater wave functions". Phys. Rev. A 55 (3): 1820–1831. Bibcode 1997PhRvA..55.1820H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.55.1820.

- Ema, Ignacio; Garcia de la Vega, José M.; Miguel, Beatriz; Dotterweich, Johannes; Meißner, Holger; Steinborn, E. Otto (1999). "Exponential-type basis functions: single- and double-zeta B function basis sets for the ground states of neutral atoms from Z=2 to Z=36". At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 72 (1): 57–99. Bibcode 1999ADNDT..72...57E. doi:10.1006/adnd.1999.0809.

- Fernandez Rico, J.; Fernandez, J. J.; Ema, I.; Lopez, R.; Ramirez, G. (2001). "Four-center integrals for Gaussian and Exponential Functions". Int. J. Quant. Chem. 81 (1): 16–28. doi:10.1002/1097-461X(2001)81:1<16::AID-QUA5>3.0.CO;2-A.

- Guseinov, I. I.; Mamedov, B. A. (2001). "On the calculation of arbitrary multielectron molecular integrals over Slater-Type Orbitals using recurrence relations for overlap integrals: II. Two-center expansion method". Int. J. Quant. Chem. 81 (2): 117–125. doi:10.1002/1097-461X(2001)81:2<117::AID-QUA1>3.0.CO;2-L.

- Guseinov, I. I. (2001). "Evaluation of expansion coefficients for translation of Slater-Type orbitals using complete orthonormal sets of Exponential-Type functions". Int. J. Quant. Chem. 81 (2): 126–129. doi:10.1002/1097-461X(2001)81:2<126::AID-QUA2>3.0.CO;2-K.

- Guseinov, I. I.; Mamedov, B. A. (2002). "On the calculation of arbitrary multielectron molecular integrals over Slater-Type Orbitals using recurrence relations for overlap integrals: III. auxiliary functions Q1nn' and Gq-nn". Int. J. Quant. Chem. 86 (5): 440–449. doi:10.1002/qua.10045.

- Guseinov, I. I.; Mamedov, B. A. (2002). "On the calculation of arbitrary multielectron molecular integrals over Slater-Type Orbitals using recurrence relations for overlap integrals: IV. Use of recurrence relations for basic two-center overlap and hybrid integrals". Int. J. Quant. Chem. 86 (5): 450–455. doi:10.1002/qua.10044.

- Özdogan, T.; Orbay, M. (2002). "Evaluation of two-center overlap and nuclear attraction integrals over Slater-type orbitals with integer and non-integer principal quantum numbers". Int. J. Quant. Chem. 87 (1): 15–22. doi:10.1002/qua.10052.

- Harris, Frank E. (2003). "Comment on Computation of Two-Center Coulomb integrals over Slater-Type orbitals using elliptical coordinates". Int. J. Quant. Chem. 93 (5): 332–334. doi:10.1002/qua.10567.

![{\partial R(r)\over \partial r} = \left[\frac{(n - 1)}{r} - \zeta\right] R(r)](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/967c035d3fb83d7857900ea69a832265.png)

![\left(r^2 {\partial\over \partial r} \right) R(r) = \left[(n - 1) r - \zeta r^2 \right] R(r)](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/7bba982a1ff81698370f0619e7c39749.png)

![\nabla^2 R(r) = \left({1 \over r^2} {\partial\over \partial r} \right) \left[(n - 1) r - \zeta r^2 \right] R(r)](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/e8d4c75eb414600f50750fbc5cec5d84.png)

![\nabla^2 R(r) = \left[{n (n - 1) \over r^2} - {2 n \zeta \over r} %2B \zeta^2 \right] R(r)](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/5241c48c3bf6ae59f325aedd0efdaedb.png)

![\int \chi^*_{nlm}(r)(-\frac{\nabla^2}{2})\chi_{n'l'm'}(r)d^3r

=

\frac{1}{2}\delta_{ll'}\delta_{mm'}

\int_0^\infty dr e^{-(\zeta%2B\zeta')r}

\left[

[l'(l'%2B1)-n'(n'-1)]r^{n%2Bn'-2}%2B2\zeta'n'r^{n%2Bn'-1}-\zeta'^2r^{n%2Bn'}

\right],](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/cc3d8595d1be12c41a5bfe9e2a660cb1.png)